This posting is lengthy, detailed and (mostly) scholarly in register. It is about the representation of Khalkha Mongol women during the soviet socialist era (~1924-1990) in Mongolia. It brushes past other relevant themes too. Sub-headings have been added to help identify points of interest. For those unaccustomed to this form of literary exposition, I recommend a strong cup of coffee (or similar) before you embark — CP.

Figure 1: The folio of essays I have written about contemporary Khalkha Mongol women. See: Pleteshner, C. (2011). Nomadic Temple: Daughters of Tsongkhapa in Mongolia (Unpublished manuscript) Location: The Zava Damdin Sutra and Scripture Institute Library Archive (Manjushri Temple, Soyombot Oron). Digital art by CP. 10 June 2018.

Genesis

In 2010, I wrote a collection of thirty-four short stories about particular Khalkha Mongol women, each of which was grounded in my own qualitative research: key informant interviews (2008 and other conversations) along with prior and subsequent participant-observation fieldwork in community with them in Mongolia between 2004 and 2010. Refer to Vignettes on this website for examples.

I applied a range of strategies to ensure a considerable degree of anonymity for study participants, the delay of publication being the final layer of this important work. Many of the women in the study are happy with being identified with their vignette, with two already being published in this form. In my ongoing consideration of what is best in terms of ethical qualitative data research and publishing practice, I cyclically return to that impasse between ethnographic researcher as well as friend-confidente. However, in my own assessment enough time has now passed for me to proceed with publishing the remaining vignettes in my folio. To my way of thinking, one can never be too careful or too mindful when writing and publishing narratives about other people’s lives using one’s own voice.

Univocal and collaborative oration

Having completed the vignettes, I began writing “during the socialist times …” upon which this article is based. It takes its title from an expression frequently used by Mongol women with whom I keep company in Mongolia. It is their cue, a means of framing, locating and setting the scene for the telling of a usually quite long and detailed story, sometimes as a single orator or at other times collaboratively with their women friends who in some way have shared experiences during this complicated time.

Whilst the vignettes capture aspects of their first person perspectives and experiences, in this post I review published scholarly, political and sociological conceptions about women in light of certain Soviet communist era agendas and moral distinctions. The particular contemporary Mongol women who inform my own ethnographic study are never too far from my mind’s eye as I write.

So you’re going to write about interpreting ‘representation’? Oh yeh …

In academic circles, methodologically, this is a thorny road to traverse given that ‘interpretation of representation’ is such a personal affair. More on this important topic further down the post. But I’d really like to share with you some soviet era images of Mongolian women (in the form of graphic art) that I think are important to better appreciating their lives, and so I am going to dip my toe into these contentious waters anyway.

In my mind’s eye are particular Khalkha Mongol women who belong to an older generation in Mongolia (in my study, those born between 1930 and 1964). My own biological mother (now deceased) and her friends in Australia from varying cultural backgrounds (from Ukraine, Poland, Germany, Latvia, Estonia, Hungary and Bulgaria) were also born into the upheaval of the 20th Century’s soviet socialist project. Russified and enculturated Soviet socialist era women to be sure. In terms of my own position-ing, this is the vista from which I now write.

Promulgating a culture of entitlement

During the soviet socialist era, moral capital, a kind of social capital rooted in defining certain values as correct and upholding them (Katherine Verdery, 1996, p106) was publicly performed, as well as controlled and manipulated as a culture of title and entitlement.

In her extensive ethnographic study of the Selenga Karl Marx kolkhoz (a collective farm in Siberia) during the 1960s, the British anthropologist Caroline Humphrey (1998a, p328; p354) describes in detail the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s localised control over the distribution of diplomas, medals and prizes to create an atmosphere in which people genuinely worked for the ideological goals signified by these awards. In this context, recognition of ‘hard work’ took the forms of people’s photographs appearing on the ‘honor board’ of a local collective, articles being written about them appearing in the local newspaper usually on recommendation of opinion leaders of the local and primary Party cell. Such ‘signs of hard work’ conferred extensive privileges. However observation indicated that the nature and also the number these given out would vary.

Each of the older generation ‘soviet era’ Mongol women in my study, those born between 1930 and 1964, have their own extensive (yet different) cache of medals. They speak of similar participative practices and outcomes to those described above.

In the earlier days of post soviet socialism in Mongolia, I observed how these women adorned their traditional Mongolian vestments (cf. deels) with medals acquired in recognition of their own merits to important (to them) public events. Within my own cohort of Mongol women, by 2010, this adornment practice had generally subsided if not ceased. These days, only older women with strong kinship affiliations to senior Mongolian army personnel and officials still wear their own collection of medals to public, commemorative (of the past) military-focused gatherings and displays. I have various photographs in my collection to this effect.

Certification, political capital, recognition and reward

In the same analysis, Caroline Humphrey also argues that there were three main avenues for advancement for both men and women during the soviet socialist era. These were in addition to the continued reliance on kinship networks and a repertoire of other conjoined strategies. These were: (a) getting oneself into a position where one was able to do hard work which was recognised, with the potential for recognition being critical to the task; (b) the building of ‘political capital’ by means of ‘social work’ (Russian. obshchetvennaya rabota); and (c) the acquiring of educational or technical qualifications.

However, such advancements for Buryat women although publicly performed (author emphasis) may well have been complicated in the domestic sphere by the socio-spiritual legacy of a Buryat intelligentsia whose descendants were from either a ‘remarkable Russian-educated elite’ or from well-to-do families oriented toward Mongolia and Tibet and the spiritual lineage connections therein.

Acquiring educational qualifications [cf. (c) above] was only a priority for some of the soviet era Khalkha Mongol women in my study. For them, travelling away from home and family (they each already had young children) to acquire certification with a view to ‘progress’ and improve their professional standing was mandatory.

They not only pursued opportunities when they became available, they also did what they were told by senior officials at local Party cell meetings. These were held in the local ‘house of culture’ that you can still find in Mongolia today. This is how they got access to otherwise unavailable opportunities (to learn and even travel abroad. As well as being mothers and wives, these women worked as pharmacists, medical doctors, teachers and geologists.

Enculturation and embodiment

However, most of these older soviet era women continued for a time to embody the practices associated with (a) and (b) as described above, as long as they were physically able and even though the socialist times had passed. One of my observations, one that I could only have realised with the passage of considerable time (2004-2016) is that, in the now post-socialist setting, these women contracted such behaviour limiting it to their now immediate kinship networks.

They each did so at a different time, as one year has flowed into the next. Given that in the new and emerging post-socialist order in Mongolia such efforts were no longer being recognised nor rewarded by the state, they tended to drift away from community-centred becoming more absorbed in other concerns: looking after grand children, in the climate of privatisation trying to get a new business up and running, engaging in all sorts of other entrepreneurial activities, that sort of thing.

In many ways, beyond immediate kinship affiliations (eg. being the mother or sister of a Buddhist prelate) I see older Mongol women’s voluntary contributions and participation in the emerging post-socialist Buddhist social and cultural sphere in Mongolia as a kind of proxy: a substitute, deemed worthy by them, for the soviet socialist form of social participation into which they were enculturated and habituated as young women. To be clear, I am not suggesting that this is the only catalyst for such participation by these older women. Nonetheless, we humans are creatures of repetition, routine, practice and at times also in need of social recognition and reward.

A ‘Russian-educated elite’

Nor has the attraction of a ‘Russian-educated elite’ lost its lustre in some Mongolian social circles today. These days it is not the social era grandmothers but their grand-children that partake, embody and seek to accumulate the social capital associated with this fare. Whilst educational institutions in Germany, China and the USA now also compete with educational institutions in the Russian Federation in the eyes of well-to-do Mongolians in Mongolia, my longitudinal research data suggests that at least one young person, if not more, from each kinship network is being sent for secondary and/or tertiary schooling to a educational or military college deemed worthy somewhere in the Russian Federation. Here, post-soviet socialist Gelugpa Buddhist revival and participation by devoutly Buddhist families coalesces with members of that same kinship network actively engaging with still-valued conceptions of a Russian-educated elite expressed and embodied by sending one’s own (grand)children to study there.

Social porosity

For some Mongolians-in-Mongolia, whilst there may be tensions, both practices are somehow harmonised across the kinship network. Rather than being seen as a contradiction, both participative associations, just as in the socialist era, continue to be at play. According to Caroline Humphrey (1998, p32)—her research remains the lighthouse for my own attempts at unravelling contemporary Mongol culture in Mongolia— the brutal destruction of the Buryat (and the Tibeto-Mongolian) Lamaist institutions during the 1930s was quite different from the persecution of the (Russian) Orthodox Church. This is because Mongolian-Tibeto Buddhism and the organisation of monasteries represented for the Buryats (as well as the Mongols she argues) not only a religion, but also the institutional form of all that was most developed in their culture; literature, medicine, the arts and education were all based in the monasteries which were situated in community.

Are we to assume then, that both Buryat Mongols started practicing Buddhism upon entering a monastic precinct and ceased doing so on their way out? As Humphrey (1998b, p431) suggests, it would be simplistic to view Soviet ideology as merely replacing localised Lamaist or shamanist thinking.

What occurred during the Soviet socialist era in Buryatia was a much more complex cross-cutting of ideas, in which Soviet elements and ideals entered into folk structures—ways of thinking which continue to survive even though their previous strong institutional induction and subsequent supports in society have virtually disappeared. Socialist era grandmothers in Mongolia now sending younger members of their family to study in Russia is yet another thread of such continuity. The socialist to post-socialist dyad is a far more porous, both socially and culturally, than historians would have us believe.

Culture, gender and responsibility for the consumption of material goods

Returning to the setting of a contemporary post-socialist Mongolia the time during which data for this study is being collected, it is difficult for performances of emerging socio-economic positioning to be completely disassociated from previously dominating cultural formations. With the formal dissolution of the use of labor as a political resource (Humphrey 1998, p300) new ‘traditions’ and ways of doing things in Mongolian society may be emerging; not all of which are solidifying around western (class) distinctions associated with conspicuous consumption of material goods.

According to Lovell (2004, p38), culture is increasingly mediated by consumption, now held to be more formative of social identities and allegiances of individuals than social class. From such a perspective, the centrality of the individual is an attractive point of departure, in that it may afford a greater recognition of personal agency. Given that ‘women’ have traditionally carried responsibility for certain aspects of consumption, the foregrounding of gender here in terms of the formation of subjectivities and identities may be useful too.

Epistemic traction

However, individualist approaches to theorizing about Mongolian women’s lives either during the socialist era (until 1990, with its social control and engineering) and during the early post-socialist period (from 1990 and for a decade or two thereafter) lacks the necessary degree of epistemic traction. Mongolian women in Mongolia are temporally and socially embedded in extensive and interconnecting blood and bone kinship networks. It is important to remember that soviet era women, who are mostly now also grandmothers, gave birth to many of children, with between six and eight each being the soviet socialist social engineering goal.

Hence in contemporary post-socialist Mongolia, whilst not all women gave birth to so many children, a more appropriate view (as baseline) is one where the family and its combined resources, rather than a collection of atomised or partnered individuals, form the basic unit of social stratification (Goldthorpe 1983, p465; p469). Here women’s positionings in relation to men in their kinship group typically form part of an overall family strategy.

In this context, a woman is considered as a person with a female body (Moi, 1999:8). In this framework, even though biological sexual difference remains in place, a woman cannot be reduced to just her female body. Rather, Moi (1999, p76) invokes Simone de Beauvoir’s concept of the body as the situation. A woman is someone with a female body … from the moment she is born until the moment she dies. But the body is her situation not her destiny.

Feminist sociological and anthropological analyses that ignore sexual difference and the social relations of reproduction do so at their peril (Lovell, 2004, p52). Doing so, with the pre and post socialist cohorts of Khalkha Mongol women who are participating in my Mongolia study, would be to miss, even obfuscate, prevailing gendered roles and their socially-scripted formations. As for their grand children born into female bodies? Individualist theorising could get epistemic traction there (although I have yet to embark on this additional work).

Gender bound up with nation-state ideation

During the Soviet socialist era, the ideation of ‘parent state to family patriarch’ promoted a particular nation-state meta-narrative regarding the social (re)organisation of gender within post-socialist Eastern European countries (Katherine Verdery 1996, p61). For this analysis, political processes in Romania are her corner touchstone.

Referring to Hungary as another national case in point, Verdery (1996, pp81-82) further argues that ‘socialism’ and ‘capitalism’ are closely inter-women as ‘variants’ of the organization of gender ‘bound up’ with a ‘national idea.’ The end of socialism brings with it an end the state assuming responsibility in terms of cost for biological and social reproduction.

Instead, such costs are decentralized and assigned to ‘households’ as in capitalist systems of socio-political governance. Verdery further contends that, ‘if the gender organization of the capitalist household cheapens the costs of labor for capital by defining certain necessary tasks (such as housework) as non-work and therefore not remunerating them, then the economies of post-socialist Eastern European economies will be viable only with a comparable cheapening.’

An end to political processes associated with socialism has also corresponded to the making invisible of certain tasks, particularly those that have become too costly when rendered visible and assumed by the state. Such tasks are feminised and reinserted back into individual households. The commodification of such household tasks (e.g. child care, cleaning, provision of meals) into a service economy, such that you now already find in advanced capitalist economies (Verdery argues) cost more and are more closely aligned with the real cost that what would be paid when these same tasks are located in the category of ‘housework.’[1] Verdery’s argument is predicated on a return to a ‘housewife-based domestic economy’ model.

However, in the Mongolian nomadic pastoralist context, I would argue that there was little shift away from the Mongolian woman as the center of the ger-household, her children and her own particular household methods (albeit varying) for organizing the day-to-day running as well as economizing during the socialist times.

Some things, such as numbers of people and locations are changing (such as the widespread drift of nomadic herders and their families to major metropolitan centres such as UB) but some things—such as access to reliable child care—have not. The older generation of women in this study speak of the difficulty in organizing (for themselves) reliable childcare for their own children during the socialist times whilst they were also required to work fulltime; paid work that also often required travel away from home.

A facilitative strategy for repression

The American sociologist and political theorist Charles Tilly (2006, pp80-81) offers us a schema for discussing the different facilitative strategies used by repressive regimes. Of the four broad-brush regime types, the ‘low-capacity non-democratic’ typology has for me the most resonance for the Mongolian women and their families during socialist times.

In ‘low capacity non-democratic regimes’, there are only (a) a few ‘prescribed performances’ for women; (b) contention (with the state regarding Buddhist practice) was expressed in hidden-forbidden (covert) performances and settings; and (c) there were high levels of violence in contentious interactions. Mongolian men who were lamas, and who were central figures in their kinship clans were executed, humiliated and/or marginalised.

Socialist paternalism

The form of relations between ‘state’ and ‘subject’ of concern here is that of a ‘socialist nation’ wherein a ‘quasi-familial dependency’ is emphasized (‘socialist paternalism’) and where ‘subjects’ of the geo-political state are presumed to be ‘grateful recipients, rather like small children in a family, of benefits granted to them by their rulers (Verdery 1996, p63).[2]

Dependency rather than agency is the ‘subject disposition’ produced. In this framing, when both ‘gender’ and ‘nation’ are deemed essential to the hegemonic projects of modern nation-state building, a prime vehicle for symbolizing (making visible something of cultural significance that would otherwise be invisible) and organizing the interface between gender and nation is the family.

Verdery argues that ‘Socialist paternalism’ constructs its ‘nation’ on an implicit view of society as a family headed by a wise Party, hence the ‘parent-state.’ In this framework, socialist society is reconfigured as an extended family, composed of ‘nuclear’ families but bound into larger familial organizations of patriarchal authority with the ‘father’ Communist Party at its head. Peculiar to this socialist model (‘zadruga-state’) implemented in Eastern Europe, was the substantial reorganization of gender roles within the ‘nuclear families’ (cf. to Goven and Dolling).[3]

Labour intensive capital poor modernisation

Verdery (1996, pp64-65) argues that the reason for this was the pushing ahead with industrialisation (hence modernisation) that was labor-intensive and capital-poor, therefore requiring every body’s labor regardless of their sex. There is, however, a crucial difference between Eastern European countries discussed by Verdery and Russia. According to Humphrey (2002, p54) in the former, the Soviet system was seen as introduced, whereas in Russia it had to be acknowledged as ‘ours.’

Russification and the rewriting of history

For Eastern European countries, as well as Mongolia, the promulgation of Stalinism into these territories in order to gain control of ethnically diverse and distributed populations was accompanied by Russification. Tensions in relation to traditional identity-making and strategies for ameliorating, if not harnessing them, became grist for the Soviet socialist propaganda machines.

In his 1998 paper, Christopher Kaplonski (1998 pp35-38) argues that the Mongolian socialist government itself was responsible for creating and propagating an identity based on the concept of ‘nation’ in Mongolia. … turning to the ‘well-recognised tactic of an appeal to, and concomitant rewriting of history.’ Kaplonski proposes that the rewriting of history (by the socialists) was ‘a particularly efficacious approach under socialism in Mongolia’, due, amongst other things, to (a) the lack of a widespread system of secular education; working in tandem with (b) the [Gelugpa] Buddhist tradition which attributes additional ‘authority’ to the written word. Traditionally, such texts take the form of liturgical and/or other Madhyamaka philosophical or commentaries texts translated and interpreted by learned ‘Teachers’ (Mong. Bagsh)

Embedded in this reading of history analysis, are two very important assumptions: firstly, that the audience/recipients of such ‘written histories’ —the Mongolians and their aimag kin-affiliates are a passive and uncritical audience. In this theory-driven approach, Mongolians (as a homogenous group) are constructed as being easily influenced nomads, or as one of the Mongolian women in the study put it, seen as ignorant and uncivilised.The possibilities of Mongolians reading such historical texts in multiple or various ways, even ‘resisting’ them, is not mooted.

The second assumption, however, is even more important: in aligning ‘national identity’ with ‘Mongolian’ twentieth century archival histories and the (potential) development of national self-awareness of the ard (commoners) (cf to Daniels in Kaplonski 1994, p38) then what of the other literacies, embodied practices and forms of Khalkha Mongol in Mongolia identity making? Where do mentor-mentee oral transmissions, most of which are not ossified into the conventional forms we associate with the documentation of socio-political histories, fit in?

Institutional discourses, because of the considerable investment required (in learning language/s, learning how to read critically and quickly with comprehension, and gaining control of the discourse through the performance of certain genres of writing for example) privilege only certain types of agency. As one of the socialist era Mongolian women in my study succinctly put it:

“Here, we all have public, private as well as secret lives.”

Using this comment as a springboard, wouldn’t adopting a ‘bottom-up’ approach to investigating Khalkha Mongol identity-making in Mongolia prove fruitful? To make this adjustment (from a top-down perspective), I refer to Ernest Gellner’s assertion (1983, p55) that:

“It is nationalism which engenders nations and not the other way round.”

In his discussion of ‘the rural’ and ‘the urban’ in a ‘pastoral Mongolia’ David Sneath (2006, p140) uses ‘elite-centralist’ and ‘rural-localist’ aligned with Bourdieu’s notion of habitus as a heuristic device to explore the ‘complexes of norms, values and skills’ in contemporary post-socialist Mongolian society. The symbiotic cultural spectrum which is constructed using this framework seems to privilege the ‘personal orientation of individuals’ in terms of lifestyle and occupational choices.

Although acknowledging that most Mongolians have social and kinship networks that cross between the rural and the urban (Sneath 2006, p156) this particular discussion nevertheless stops just short of considering the complementarity of those same individual personal orientations in relation to each other and within the context of their extended kinship groups across the rural-urban spectrum and beyond.

As Ole Bruun and Li Narangoa (2006, pp15-16) point out, ‘social networks in rural districts have long crossed the boundaries between mobile and settled aspects of Mongolian life, with both products and people, particularly children, moving between settlements and the mobile pastoral encampments to create a social matrix that links [not only] local rural and urban contexts, but with affiliated kinship networks located further afield in larger political and economic urban centres as well as overseas.

Rural and urban: is it a divide? Or rather a matrix of interconnecting affiliations?

Drawing on Bourdieu’s notions of (separate) streams of socio-cultural reproduction to describe recurrent themes in Mongolian social change (Sneath, 2006, p140-41), rather than a general ‘dualistic treatment of rural and the urban culture,’ actual inter-connections could also be explored. Bourdieu’s emphasis on reflexivity as a prerequisite to knowledge reminds us to be vigilant of the boundaries and hence limitations of the espistemic positions from which we speak (cf. to Skeggs 2004, p21).

Soviet socialist urbanisation, modernisation, industrialisation and more

During the socialist times, the Mongolian State undertook an ambitious program of urbanisation and industrialization supported by considerable investment from the Soviet Union. In the process, the socialist political system had generated a Mongolian variant of the dominant Soviet political culture and integrated the Mongolian elite, to some extent, into the national elite of the USSR. In addition, Marxist values were ‘powerfully promoted’ by the educational system and the mass media (Sneath 2006, p146; p147).

Although this ‘center-focused complex’ of a ‘field of knowledge’ was neither uniform nor totalising, it did offer Mongolian people contrasting aspirational content, alternative notions of self-worth, aesthetic value as well as alternative and publicly performed pathways for personal fulfilment (further Sneath 2006, p147).

Working from a foundational premise of Marxist dogma where industrial workers would lead ‘socialism’, state socialism reinforced further the identification between political centers, elites and the city by investing heavily in urban and industrial centers and ways of life associated with them. Industrial workers were promoted as both the heroes and the leaders of the revolution.

Lots of statues, stories and books about man-heroes right?

But what of the inspirational images of Mongolia’s female socialist protagonists?

What do they look like?

So what about them?

One of the primary vehicles for promoting such a ‘national allegory’ was a genre of art referred to as ‘socialist realism.’[4] David Sneath (2006, p148) also suggests that ‘the appeal (to the Mongolian people) was relatively non-gender specific, although senior Party posts were still largely held by older men.

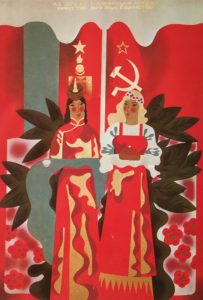

The espoused ideology was one of gender-neutral meritocracy. However, as Figure 2: Scientific development and industry brings a new life (1932) illustrates ’[5 ] this was not always the case. Where are the boys in this picture? Also, enter, stage left: the hand-powered sewing machine … to sew military uniforms for Russian soldiers perhaps?

Figure 2: Original Russian text: “Развитие науки и промышленности приводит к новои жизни” (“Scientific development and industry brings a new life”). Banner by Гэнгоржав. (1932). Plate no. 32 in the Плакаты (Poster) Chapter of “Графика Монголии” (Mongolian Graphic Art) Edited by Д Майдар (Москва, 1988). ISBN 5-85200-007-8. Dimensions of the original banner not specified.

Socialist Realism

As the official art form in Soviet Russia from the mid-to late twentieth century, and later by allied socialist parties worldwide until 1990, in the years following 1924 in Mongolia, ‘socialist realism’ [6], a style of realistic art, became one of the primary vehicles for disseminating Joseph Stalin’s vision of Communist ideology.

Visual (rather than literary) narratives seemed well-suited to a Mongolian populace not yet literate in Cyrillic Russian, the language of Soviet socialist propaganda. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s Soviet artists and teachers introduced their art in Mongolia and a number of Mongolian artists were sponsored to train in the Soviet Union.

Through such cultural exchanges Mongolian artists learned to use oil paints and became familiar with socialist realism, as well as 19th century Russian Realism and Impressionism. Socialist Realism was dominant during the socialist regime, depicting the lives of the people working hard together to develop the country. Mongolian artists were still going to live and study in Moscow to be formally trained as artists in these genres until as recently as the 1980s. (Soloymaa’s story from Nomadic Temple illuminates this point).

It seems we have finally arrived at our interpretation of visual representation destination ….

Гэнгоржав’s banner can be interpreted as introducing (through visually deconstructing familiar-to-Mongolian people associations of known elements and at the same time strategically introducing new ones into a pastiche), a ‘rural-localist’ and ‘elite-centralist’ heuristic (cf. Sneath 2006), the lines along which socialist reconstruction would progressively unfold.

The now complex pastiche of disassociated symbols, images and motifs conflates rural with urban, pre-empting, even promulgating a notional shift towards centralised power and its institutions from the prevailing sparsely-distributed nomadic-herder pastoralist distribution of Mongolian people across the grassland steppe,; something that was a temporal and social reality for them. And far from being a gender-neutral normative framework, this 1932 banner is so gender-role specific Where are the people in male bodies? Aren’t they going to be sewing too?

Although the actual dimensions are not specified, the banner appears to be quite large (note the fold lines) and therefor transportable. In terms of the social life of this material object, it may well have been carried from one to yet another community gathering, in time through the network of Soviet houses of culture (see Marsh 2006) to be established perhaps? These were instituted as the primary nodes of socialist community (re)construction, located in the urban centre of each of then 300 sums (local districts) distributed by the Communist Party across the Mongolian steppe.

One of the threads to my interpretation of this Soviet socialist representation of the two women, one Russian (left) and the other Mongolian (right), is that they are depicted as being central; as progenitors and protagonists of the socialist industrialisation agenda through State institutional infrastructures and across the then imagined Mongolian-rural to industrialist-urban divide. According to Jacob Emery (2008, p164) in the Stalinist epoch, the figures of young woman about-to-be if not already mothers and nation were recuperated. Posters extolling ‘Mother Russia’ (mat-Rossiia) and the ‘motherland’ (Rodina-mat) became commonplace.

Embarking on modernization through: (a) ‘advancements’ in education; note the folder ‘embraced’ by the Mongolian woman’s left arm; (b) adopting a different mode of production; through mechanisation, of which the Soviet-introduced hand-powered sewing machine is a key and strategic example; and (c) collaboration and cooperation; note the right hand outstretched in a gesture of acceptance.

Mongolian womanhood could now take up the baton of soviet socialist mechanisation in the context of industrialisation whilst still looking after the kiddies playing at her feet. The image is an empowering and positive one. There is no visual narrative alluding to possible punitive measures for non-adoption (of new technologies) or non-compliance. The outstretched hands of both parties present the image of a smooth transition and done deal; a faits-accomplis.

In rendering the above interpretation, I may have gone too far since the relation between what we see and what we know is never settled (Berger 1972, p7). For although images are indexical of social reality and have something to say about society, such socialist realist propaganda should not be read as equivalent to Mongolian social reality during the socialist times.

Nothing is known about how the banner’s intended audience read this visual text. I am making the assumption that the intended audiences for this socialist banner were Mongolian women and men. However, I could be mistaken: the main audience may have been [just] women or [just] the State patronage for whom the banner was created by the artist. The politics of artistic production is nevertheless implicated.

I have yet to show this or other soviet socialist banners to the Mongolian women in my own ethnographic study, using it as a point of departure to stimulate exploratory conversations that inevitably take us elsewhere. Mongol women of this older generation are such interesting people! Given that time is running out, maybe one of you would like to try out this methodology in one of your own data collection strategies, one-on-one or in a group? — CP

Projecting ideological dimensions onto womanhood

So how do we work with visual, as well as literary, narratives that are intended to project a political dimension of womanhood in the form of national allegory where the story of the private individual is an allegory of a socialist and embattled situation for public culture and society? (cf. to Bernstein 2008, p1).In what sense is the above banner a national allegory? Is it, to some degree, allegory as fabrication, even social fiction? Is this an image that was first made to conjure up the appearance of a socialist something that was absent? (cf. to Berger 1972p10). Or, is it tapping into aspects of Mongolian womanhood and [re]establishing their place in a new and imaginary social world?

Mother as nation

There are innumerable ways in which to explore cultural narratives connecting notions of womanhood, particularly motherhood and the mother’s body to the ideas of community and nation; not only to establish the concept of ‘nation’, but t times to challenge the idea of ‘nation’ as an ‘imagined community.’

According to Bernstein (2008, p211) the notion of mother-as-nation spans time and cultures. ‘Mother Russia’ and ‘Mother India’ are familiar terms through which we imagine the nation as mother to her citizen children. From creation myths to symbolic mother countries, fertility goddesses and mothers of religious deities, the maternal body has been used to represent national communities across geographical regions and historical periods. And so, under which conditions have Khalkha Mongol women in Mongolia been permitted to enter public discourse and political activism as mothers? Are we looking at a prototype of a Soviet socialist construction of the ‘Mother Mongolia’ ideal?

It may be sobering and realistic at this juncture to draw on Katherine Verdery’s summation (1996, p65) of how, in Eastern European countries under socialism, socialist women came to bear the ‘triple burden’ of housework, mothering and wage work; where unpaid household labor became the responsibility of pensioners, who cared for grandchildren and cooked for younger members of the family who worked for wages.

In my early days of fieldwork, the older soviet era Mongolian women in my study spoke to me of how they juggled these competing responsibilities for so many years. (These preoccupations have been overtaken by other interests now). In such a socialist framing however, it was quite difficult for me to imagine the circumstances wherein a Mongolian women’s existing and routinised animistic-Buddhist spiritual practices could be sieved, separated out, quarantined, ‘preserved’, from her considerable other social, familial, and now also, it would appear, increasingly public socialist-political obligations to the State.

In fact, many of the Mongol women in my study spoke of their ‘commitments of continuity’ as if this was a fourth (and therefor additional) stream of responsibility, to be carried along with all of the rest. Let me tell you, these particular Mongol women are so tough. Their demonstration of resilience during this demanding time is simply remarkable!

Lisa Bernstein also argues that the experiences of actual women and their ‘mother’s stories’ are often missing from the prevailing discourse of national motherlands.[7] Drawing on evidence from literary and social discourses to build her argument, Bernstein (2008, p211) concludes that the figure of the mother as nation-state allegory has been used at times for both imperialist expansion to represent the nation (for the purposes of constructing national identity), or to envision new and different concepts of community and social space beyond the idea of the nation-state, which seems to me more applicable to understanding the situation for Mongol women in Mongolia during the socialist era under discussion here.

She also cautions us to be mindful that the inscription of ‘the mother’ as national allegory contrasts dramatically to women’s historical, systematic exclusion from the sphere of public national life. In terms of how this summation may apply to Mongolian women in Mongolia during the socialist era, I make no claim to insight. However, I can offer you an illustrative example that supports Bernstein’s assessment from 2008, nearly 2 decades after the cessation of socialism in Mongolia. In Mongolia’s 2008 national election, only three women (Dashjamts Arvin, Sanjaasuren Oyun and Dulamsuren Oyunhorol) were elected to a seat in the Mongolian parliament, the State Great Hural. At that time, there was a total of 76 seats representing 26 multi-member constituencies.[8]

National allegory

The term ‘national allegory’ has been attributed to Marxist literary critic Fredric Jameson (1986) who used it in a very particular way.[9]Jameson (1986, p69) argues that national allegories are displayed in texts that are the products of western machineries of representation: reflecting capitalist culture, there is a split between the private and the public, amongst other things. We (as westerners), according to Jameson, have been trained in a deep cultural conviction that the lived experience of our private existences is removed from and incommensurable with the abstractions of economics and political dynamics. An interesting perspective. What do you think?

But what if one’s family and life are subject to, or subjects of, a totalitarian experiment in political domination —such as the extended Soviet socialist project in Mongolia—undertaken by a revolutionary movement, with an integralist conception of politics? (Emilio Gentile 2000, p19).

In such ‘revolutionary anthropological experiments’, instruments such as demagoguery were exerted through constant and all-pervasive propaganda and the mobilisation of enthusiasm. Coercion is imposed through violence and totalitarian pedagogy is institutionalised and delivered at a high level and according to male and female role models, developed according to the principles and values of a palingenetic (rebirthing) ideology. The discrimination against outsiders is undertaken by way of coercive measures: that from exile from public life to the physical elimination of human beings, who, because of their competing (for example, ‘religious’) ideas are considered enemies of the objectives of the totalitarian experiment and therefore are regarded as undesirable (Gentile 2000, pp20-21). If aligning with this perspective, the early socialist banner (1932) titled ‘Scientific Development and Industry Brings a New Life serves as an example of totalitarian visual pedagogy and propaganda designed to affect mobilisation of the imagined industrialised female workforce.

Another nuance of soviet socialism to consider

Gentile (2000, p21) also proposes a kind of religious dimension to the politics of such totalitarian states; even a sacralisation of politics, a term, he argues, that neither applies to theocracies [in Mongolia’s case, my interests relate to Buddhist lineages] or to regimes governed by traditional religions (Gentile (2000, p22). I step back from referring to ‘Buddhism’ in Mongolia as a ‘traditional’ religion given that the interwoven fabric of beliefs and practices there, especially amongst the Khalkha women I have come to know and have met over the years. It is more complicated and variable than the categorical descriptor ‘tradition’ infers.

A religious dimension is instituted when politics is conceived, lived and represented through myths, rituals and symbols that demand faith in the ‘sacralised secular entity’ such as, in this current context, a State institutionalising Soviet-styled socialism. For such a religious dimension’to be invoked, socialist politics (and those who are its protagonists) must have secured its autonomy from traditional religion—which for Mongol peoples populace includes, but is not limited to, Buddhism, Tengrism, Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, ancestor worship, poly and monotheism) by secularizing both [Mongolian] culture and the [Mongolian] state.

According to Gentile (2000, pp23-24) ‘religion of politics’ interpreted as ‘civil religion or political religion’ (Gentile 2005) is mimetic. In this sense,it draws from the systems of creating beliefs and myths, dogmas and ethics from traditional religions. And although the phenomenon of such a sacralisation of politics is considered to be have been most intense during the inter-war years ie between WW1 and WW2, the syncretic aspect, that of incorporating the traditions, myths and rituals of traditional religion and adapting them to its own mythical and symbolic universe is very much worth considering here.

Figure 3: Russian text (second line): “Братство Дружба Единство.” (“Brotherhood, Friendship, Unity”). Original Mongolian text (top line): Ах дүү ёс, найрамдал,нэгдэл. Poster by Н Амгаланбатар (1984). Plate no. 49 in the Плакаты (Poster) Chapter of “Графика Монголии” (Mongolian Graphic Art) Edited by Д Майдар (Москва, 1988). ISBN 5-85200-007-8. Dimensions of the original not specified.

Figure 3: Brotherhood, Friendship and Unity is a poster painted by the Mongolian national artist Н. Амгаланбатар under State patronage more than 50 years ago (1983) into the soviet socialist project in Mongolia.It exemplifies the creativity and artistic exactitude that an experienced artist can bring to a particular work performed within the tightly scripted constraints of a particular genre (ie.socialist realism). The inclusion of the latter work is testimony to the resilience of the syncretic formulas of socialist realism as administered.

This is another visual arts example of soviet socialist central and integralist conceptions applied to the creation of propaganda. In this poster, both Mongolian and Russian women are implicated, a visual construct common to many such works. We’ll put aside for now the fact that although the poster depicts two people in female bodies, the title of the work (as translated) begins with descriptor ‘brotherhood’. Here, I wonder if a retrospective analysis through the lens of feminist anthropology and its contemporary western conceptions has a role to play …

Bread

In the poster, the woman on the right is Russian. She holds a loaf of bread. Caroline Humphrey (2002, p57)— yes, she’s back! As I have already mentioned I never venture too far from her meticulous and insightful works—refers to bread as having symbolic value for Russian peasants before the Revolution in 1917. It was offered, together with salt, to welcome visitors on behalf of the village community. During the Soviet socialist period in Russia, bread came to epitomise food. In the context of experiencing war as well as hunger, for some ‘bread’ became something almost sacred.

Bread, as well as some form of libation, is being offered to the viewer. Rather than the larger vessels into which Mongolian mare’s or other milk is decanted by Mongolian people, the young Russian woman holds a drinking vessel akin to the small size from which say a shot of vodka? could be consumed. The young Russian women is foregrounded. Her right shoulder is positioned just in front of the young Mongolian woman to her left, so that she appears to be leading. Through this lens a closer viewing reveals that this syncretic interpretation by the artist has privileged the Russian. Here I wonder what the older Mongolian women in my study would have to say about this work?

Painted in 1984 not long before the final collapse of the Soviet Union (1989), rather than a Mongolian Buddhist blue khatag, here the khatag is rendered in a colour green; possibly a hue more synonymous with that of the fields of young wheat and rye crops from which after harvesting the bread is then made. Here issues of colour reproduction quality may also be of concern …

Nevertheless, a khatag, now green in colour, is being offered to us, the people, by the young Mongolian women. Having been disassociated from its original colour (blue) and ritual presentation—to one’s lama, one’s own beloved father or mother for example—the ritual khatag is now deemed secular, both in terms of its depiction and its intended (imagined) audience-recipient. The view to the communist hammer and sickle (top right) is complete and clealry visible, whereas the view of the Mongolian flag with its soyombo[10](see Atwood 2004, pp518-19) is partially obscured..[11]

Enlisting these two young women; one as a Mongolian (left) and the other Russian (right) as a national allegory, a political bipartisan approach is (kind of) represented. Although syncretic, a power relations differential of superior (Soviet) to subordinant (Mongolian) is portrayed. Although ‘sisters’, the young Russian woman depicted here in Figure 3, with her long flowing blond hair is the more mature of the two. See her curvaceous form and plump bosoms?

Unlike the two representations of women, one Russian the other Mongolian, in the early 1932 propaganda banner (Figure 2) where the sexuality of both female bodies has been downplayed, in Figure 3 the sexuality of the young Russian woman is foregrounded. Here, there is no sign of androgyny; nor ambiguity as to the gendering of the people (female) and the provision of service through the offering of substances (food and drink) with which women in both cultures are conventionally associated (Emery 2008, p165). With a communist red the dominant colour, schematically, their social presence has been developed by the artist within a limited space (cf. to Berger 1972, p46).

Figure 4: Original Russian text: “Добро пожаловать!” (“Welcome!”) by Я. Уржйнээ (1980). Plate no. 137 in the Станковая Графика (Machine-printed Graphic Art) Chapter of “Графика Монголии” (Mongolian Graphic Art) Editeed byД Майдар (Москва, 1988). ISBN 5-85200-007-8. Dimensions of the original artwork not specified.

Specialising in Russian history, Elizabeth Waters (1992, p124) has pointed out that these kinds of metaphors can also be read as proceeding from the pre-Stalinist period, where Soviet propaganda availed itself of the therapeutic possibilities of young, beautiful and female figures of motherhood offering succour; a cup of milk in a time of considerable social upheaval and change. Here, the iconic conflation of mother and motherland, family and state are deemed to serve, humanise and legitimise the communist Party, even if that conflation is never actually completely successful. Here we begin the interpretation of representation Figure 4: Welcome.

These somewhat instrumental perspectives offer a complicating narrative to what early documented codes of Soviet law were espousing. According to Benwell (2006, p136 no.16) the status of both women and men in the socialist period was ideally equal with Soviet 1918 Code of Law abolishing the inferior position of women at the time. Even now, it is rare to see men in Mongolia offering food and drink, unless that is, they are a restaurant owner or waiter in now-cosmpolitan UB. I digress …

The above machine-printed poster was also published towards the end of the soviet socialist era in Mongolia although it appears to have been drawn by Я. Уржйнээ well before then. There are many symbolic and other elements of interest in this composition. Here I’ll touch and speculate upon a few.

Dressed in a highly-stylised depiction of a well-to-do young Mongolian woman’s traditional vestments and adornments (note the hat and traditional draping of pearls to frame the face), she is ready, poised and waiting for someone: you, us, the voyeur, the outsider, the unknown and anonymous ‘other’? Her deel (traditional dress) is red in colour. Is it the red associated with the soviet socialist community part? Or is it the innovative red of the deels worn by Mongol women who were coming out as Buddhist nuns at the onset of post-soviet socialist change?

Solid in her footing her arms are open and outstretched as she balances a traditional silver and timber (often walnut) bowl of mare’s milk (arag) in her right hand atop a blue khatag (Buddhist offering scarf). What kinds of messages does this presentation of her posture convey? Openness? Confidence? Accomplishment? Stability? Or welcoming change?

The young Mongolian woman’s stance is outwardly open and inviting. Amongst my Khalkha Mongol friends in Mongolia (women and men), the image of her palms facing upwards (towards the heavens) is an often-used culturally-constructed gesture and embodiment for them. ‘Welcoming’ is but one use of this form.

It is reasonable to say that our interpretation of the meaning of this gesture would depend on our situated-ness and context at the time of its presentation. It also depends on who we (the intended recipients) are. Supplication, acknowledgement and making a request are other interpreted meanings associated with this same gesture.

Her stylised features are elongated. Note her tall slim body, her long arms, elongated neck (swan-like) hands and fingertips? Are we to interpret this through the lenses of Buddhist iconography? Or is this particular representation of a young Mongolian person’s womanhood better aligned with newly encroaching notions of beauty and elegance such that prevail in the west? Her skin is rendered pale in colour not dark as it would be in real life … she is rendered thin—with not an extra gram of body fat in sight.

In a soviet socialist framing, the ‘milk’ in her vessel could also have considerable symbolic force. In this framing, a mother’s ‘nursing’ represents the individual’s first participation in the social economy (see Ransel 1988, p235). Further to a socialist framing, the inclusion of common symbols associated with the electrification and industralization of Mongolia’s ‘landscape’ (note the various elements in the background) integrates into a figurative system the idea of milk as a ‘pre-eminent form of food’ (see Emery 2008, p165). During my many years of fieldwork in rural Mongolia, I have rarely entered a nomadic parstoralists main or kitchen ger (yurt) where there wasn’t a big cauldron of fresh milk placed on top of the central stove or fire boiling away. It is from this central position that the matriarch of the household, as she constantly stirred and aerated the milk with her ladle, held court.

In this poster, the inclusion of an image of a blue Katag establishes a Mongolian differentiation marker. Here the association is with Mongol (not Tibetan) Buddhism. Here the khatag is blue. In Tibetan Buddhism the kata is white. The incorporation of the khatag (as a symbolic element) in itself is an innovation. It differentiates this artwork by a Mongolian artist from many of the other soviet socialist posters I have seen.

With one of Mongolia’s four holy Buddhist mountains which surround Ulanbaator visible in the background (left) the image of the sky is heavy and pregnant with potential, as if there is about to be a downpour of some kind. Perhaps of welcome rain for the grain being cultivate in the pastures? But this idea would be limited to the fertile soils of Selenge Aimag of course. Possibly of the preeminent substance contained within the vessel perhaps? We can speculate wildly on what that could be! Or maybe this wonderful poster tries to capture the idea of ‘Mongolia’ on the cusp of soviet socialist to post-socialist change with the sky symbolising the massive and turbulent social upheaval on the way.[12]

Question: What do you see in these three artistic representations of Mongolian womanhood? What are they saying to you?

This article is dedicated to my dear friends Jantsan Gundegmaa and Yadamjav Sumya who over the years have been unfaltering in their perseverance and personal generosity towards me and so many others.

References

Ahmad, Aijaz. 1987. “Jameson’s Rhetoric of Otherness and the ‘National Allegory’.” Social Text(17):3-25.

Anton, Lorena. 2008. “Abortion and the Making of the ‘Socialist’ mother during Communist Romania.” In (M)Othering the Nation: Constructing and Resisting National Allegories through the Maternal Body, edited by Lisa Bernstein, 49-61. Newcastle, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Atwood, Christopher Pratt. 2004. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and The Mongol Empire. In Facts on File Library of World History. New York: Facts on File Inc.

Atwood, Chrsitopher Pratt. 1994. “National questions and national answers in the Chinese revolution: or, how do you say Minzu in Mongolian?” Indiana East Asian Working Papers(5):37-73.

Berger, John. 1972. “Ways of Seeing.” In, 10-11. London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books.

Bernstein, Lisa. 2008. “Saving the Motherland?” In (M)Othering the Nation: Constructing and Resisting National Allegories through the Maternal Body, edited by Lisa Bernstein, 160-172. Newcastle, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Bulag, Uradyn Erden. 1998. Nationalism and Hybridity in Mongolia, Oxford Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology. New York: Clarendon Press.

Emery, Jacob. 2008. “The Land of Milk and Money: communal kitchens and collactaneous kinship in the Soviet 1920s.” In (M)Othering the Nation: Constructing and Resisting National Allegories through the Maternal Body, edited by Lisa Bernstein, 160-172. Newcastle, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Gellner, Ernest. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gentile, Emilio. 2000. “The Sacralization of Politics: definitions, interpretations and reflections on the question of secular religion and totalitarianism. Translated by Robert Mallett.” Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions1 (1).

Gentile, Emilio. 2005. “Political Religion: a Concept and its Critics – a critical survey. Translated by Natalia Belozertseva).” Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions6 (1):19-32.

German Propaganda Archive. 1988. Kleines politisches Worterbuch (GDR Political Dictionary): Neuausgabe. Berlin: Dietz Verlag pp17-18; 795-797.

Goldthorpe, J. 1983. “Women and Class Analysis: in defence of the conventional view.” Sociology17 (4):465-488.

Humphrey, Caroline. 1998a. “Politics in the Collective Farm.” In Marx Went Away – but Karl stayed behind. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Humphrey, Caroline. 1998b. “Ritual and Identity.” In Marx Went Away – but Karl stayed behind. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Jameson, Fredric. 1986. “Third-Wolrd Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism.” Social Text(15):65-88.

Marsh, Peter K. 2006. “Beyond the Soviet Houses of Culture: Rural Responses to Urban Cultural Policies in Contemporary Mongolia.” In Mongols from country to city: floating boundaries, pastoralism and city life in the Mongol lands, edited by Ole Bruun and Li Narangoa, 290. Copenhagen: NIAS.

Ransel, David L. 1988. Mothers of Misery: child abandonment in Russia. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Shagdarsuren Oyunbileg, Nyamjav Sumberzul, Natsag Udval, Jung-Der Wang, and Craig R. Janes. 2009. “Prevalence and Risk Factors of Domestic Violence among Mongolian Women.” Journal of Women’s Health18 (11):1873-1880.

Skeggs, Beverley. 2004. “Context and Background: Pierre Bourdieu’s analysis of class, gender and sexuality.” In Feminism after Bourdieu, edited by Lisa Adkins and Beverley Skeggs, 19-24. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Sneath, David. 2006. “The Rural and the Urban in Pastoral Mongolia.” In Mongols from country to city: floating boundaries, pastoralism and city life in the Mongol lands, edited by Ole Bruun and Li Narangoa, 140-161. Copenhagen: NIAS.

Stalin, Joseph. 1942. Order #227 (28 July 1942) by the People’s Commisar of Defence of the USSR. Transcribed and translated by Soviet Russia Today. Available at: http://www.mishalov.com/Stalin_28July42.html.

Szeman, Imre. 2001. “Who’s Afraid of National Allegory? Jameson, Literary Criticism, Globalization.” The South Atlantic Quarterly100 (3):803-827.

Tilly, Charles. 2006. Regimes and Repertoires. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Verdery, Katherine. 1996. “From Parent State to Family Patriarchs.” In What Was Socialism, and What Comes Next?, 61-82. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [Princeton Studies in Culture/Power/History. Edited by Sherry B Ortner, Nicholas B Dirk and Geoff Eley].

Waters, Elizabeth. 1992. “The Modernization of Russian Motherhood 1917-1937.” Soviet Studies44 (1).

Witte, Susan S, Altantsetseg Batsukh, and Mingway Chang. 2010. “Sexual Risk Behaviors, Alcohol Abuse, and Intimate Partner Violence Among Sex Workers in Mongolia: implications for HIV intervention development.” Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community38 (2):89-103.

Footnotes

[1] Verdery (1996, p82) also advocates that as the transition [away] from socialism continues, scholars should be especially attentive to how nationalist politics integrates gender [and] the alternative forms of national imagery that are being offered and by whom … [therein] producing distinctive forms of democracy and capitalism in which nation and gender are intertwined in novel ways.

[2] Verdery’s narratives circle around women, reproduction and abortion as a means of social engineering in Romania during (post) socialist times. On this topic, also see Anton (2008). However, the topic of abortion did not come up, nor was it raised, during my fieldwork with Mongol Buddhist women in Mongolia.

[3] Verdery (1996, p245 no.15) notes the general lack of availability of family/gender configurations from one or another Eastern European society prior to 1945. That being the case, it is difficult to comment on to what extent the family/gender configuration patterns continued or differed from something earlier.

[4] Socialist Realism is such an interesting topic. Joseph Stalin’s control of all artistic production (music and the arts) and its consumption, the establishment of both a Writers Union and an Artists Union (associations that were neither free nor predicated on a guild model), its use to bring ethnically different nationalists into the soviet social and political sphere, the social reality that the State became the sole ‘benefactor’ and source of income for artists (State patronage), and the use of socialist propaganda in Mongolia in particular to appeal to people’s goodness and hope for a better future all require more attention that I am able to give here.

[5] I wish to thank my translator and now long-time Mongolian friend Damdin Gerelbayansgalan for the many hours she allocated from her own busy schedule for us to visit and search through the many small bookshops and street markets that were in UB during my early years of fieldwork looking for interesting books. It was during one of these excursions—its was late in the day, we were tired and hungry, the sun was setting and the temperature outside was dropping— when we stumbled across a second hand copy of Mongolian Graphic Art from which this image of a relatively early soviet socialist banner was drawn. I found it amongst a pile of other old books set out on the ground by a less than well-to-do elderly Mongolian man who was selling his family’s small collection of books accumulated over a lifetime to buy food and fuel. The early 2000s was a very tough time for most Mongolians, financially. I have never forgotten this exchange and my privileged position in the transaction. In terms of considerate (if not ethical) anthropological research practices, rather than just letting this particular book continue to sit on the shelves of my own library’s collection, I really wanted to invoke its use by sharing with others selected elements drawn from its contents. In some way methodologically, doing so brings a sense of satisfaction as well as completion for me.

[6] Search The Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) open access online catalogue using the search term ‘socialist realism’ at http://www.moma.org/collection/theme.php?theme_id=10195 [Accessed: 10 June 2018].

[7] As an example, during the depths of Word War in his important speech (an appeal to the people) Joseph Stalin (1942) invoked ‘the Motherland’ and not the State in an attempt to rally his civilian and other troops. Stalin moved to using symbols of pre-Soviet nationalism, which had previously been rejected as bourgeois. ‘Motherland’ rather than having disappeared, was for strategic geo-political purposes re-invoked. Once the war had been won, however, the central propaganda machine reverted to Marxist-Leninist formulas (see German Propaganda Archive 1988).

[8] In the relatively short history of the Mongolia’s democratic parliament, the greatest number of women were elected in the 2004 election; at which time nine women were elected. Since 1990 when Mongolia’s democratically-elected parliament was established, 3 Mongolian women have already reached the position of Minister: N. Bolormaa (Minister for Education, Culture and Science); Dr. Sanjaasuren Oyun (who is a sister of an assassinated in 1990 at the age of 36 Mongolian democratic leader Sanjaasuregiin Zorig) was Minister for Foreign Affairs; and T. Gandi who was (Acting) Minister of Labor and Social Welfare. However, According to Benwell (2006, p136 no.17) an unofficial list of the 2004 Mongolian parliament elections lists only three women, i.e. 2.28 percent.

[9] Jameson’s position has been challenged by some post-colonialist theorists (see Ahmad 1987, Szeman 2001).

[10] The Mongolian ‘soyombo’ is derived from the Sanskrit ‘svayambhu’ (self-existent).

[11] According to Bulag (1998, p238) both the Buddhist lotus and the Soyombo are invoked by different political groups in their contention for power.

[12] Other feminist scholars might impute a less abstract, less wholesome reading of this womanhood-as-allegory visual narrative. Lisa Bernstein (2008, p231) suggests the ‘mother-as-allegory’ narrative of men saving [the nation] conceals somewhat pervasive state-sanctioned violence against women, even as it reveals the danger of dividing women and men into ‘life givers’ and ‘life takers.’ Such separation on a metaphorical level may predispose us to see ‘all women’ as ‘naturally’ peaceful and to condone men as ‘naturally’ aggressive and thus unable to control their violent behavior. Domestic and other violence towards Mongolian women (Witte, Batsukh, and Chang 2010, Shagdarsuren Oyunbileg, Nyamjav Sumberzul, Natsag Udval, Jung-Der Wang, and Craig R. Janes 2009 )is a real problem.

Author’s Notes

- The text of this article is an edited extract from the third chapter of Nomadic Temple: Daughters of Tsongkhapa in Mongolia (C.Pleteshner 2011, unpublished manuscript: 365pp). The Zava Damdin Sutra and Scripture Institute Library Archive in the Manjushri Temple, Soyombot Oron).

2. The first image (Figure 1) in this post is an artistic representation of the Nomadic Temple tome and the Mongol women’s stories that have shaped its form.

3. To the best of my knowledge, the scanned images represented here in Figures 2, 3 and 4 for educational and non-commercial purposes does not breach Soviet Union original artist copyright law. Mongolian Graphic Art, a bilingual—Russian Cyrillic (primary) and Mongolian Cyrillic text, with photographed images of artists’ original works was edited by D. Maydar and published in Moscow by Izobrazitel’noye iskusstvo Press in 1988.

4. In this post I thought it important to retain at least some of the Russian Cyrillic text in order to reflect some of the processes of Russification (in this case language) promulgated during the soviet socialist era in Mongolia and where the older generation of Mongolian women were at the time culturally immersed.

5. If you’d like to explore the topic of Soviet socialist-era graphic art in Mongolia further, as a point of departure a copy of the book Mongolian Graphic Art and other compendiums of original artistic works by ethnic Mongol artists may be located in The Mongolian State University of Arts and Culture‘s extensive library collection. It is likely that The National Library of Mongolia has a copy of this soviet era publication too. The Mongolia and Inner Asia Studies Unit (MIASU) Cambridge University has listed Mongolian Graphic Art in their own library’s 2017 catalogue (A29). The American Centre for Mongolian Studies (ACMS) also has a copy in their collection (Call no. NC359.M6 M254 1988).

6. And finally, if I have made any errors in understanding or judgement in writing this manuscript, they are of course my own.

Artscape 07: During the Socialist times was researched and written by Catherine Pleteshner.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2024. CP in Mongolia. This post Artscape 07: “During the socialist times …” is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 12 June 2018. Last updated: 20 June 2022.