Early morning view from the south-facing footsteps of Migjid Janraisegiig Temple (Janraiseg Datsan; Tib. mig-’byed spyan-ras gzigs-kyi grwa- tshang) overlooking the Gandentegchinlen (Ganden Monastery) precinct in Ulaanbaator, Mongolia. Photograph, sepia: C Pleteshner. 21 August 2004.

Mongolian women with whom I have spent considerable time since 2004 have taken it upon themselves, as our friendships have developed, to share with me deeply moving stories about the challenging and often difficult circumstances they encountered during the socialist times. In this post, I have selected two personal accounts to ground us in the social and political realities of what it is like to live under a totalitarian regime. I have a folio of similar stories. There is no moving forward without understanding at least some of the past.

Attaining Buddhahood is the ultimate do-it-yourself project!

These two socialist era[1] women’s stories appear here distanced from their narrators. This is to ensure de-identification and therefore both the security and the privacy of the two individual women concerned. These accounts recorded in 2008, although translated and transcribed into English from the orated Mongolian, are rendered verbatim.[2] Here, the women speak for themselves. My Mongolian women-friends and I refer to these as for the record stories; personal narratives that unless documented, would not get onto the pubic record, thereby leading to the incorrect assumption by others that the situated events they describe did not take place.[3]

There is one thing that I have kept a secret, but I really want to share with you now. I still have such deep feelings of hatred in my heart for what happened. The [soviet socialist] system just destroyed so many things. My own parents were victims of it, and as we were children at the time, we have felt it, and have had to live with the consequences our whole lives.

My own father was forced to hide his religious stuff; whatever and absolutely everything he used, up in the mountains. He kept this secret with him his entire life and never told us! He left this world with this secret. I begged him to tell me the place where he buried his things. But he told me not one word. I could feel his fear for us, his children. He was scared that our knowing, or having these things could cause us, his own loved children, problems.

When he was so sick, I said to him, ‘Daddy, you are dying now, so please, please tell me where did you hide your things?’ But his reply was, ‘You my child, do not need to know that.’

We could feel how it was so incredibly difficult for him, what thoughts he was carrying his entire life and how faithful he was. Whenever I think back to this, I always feel deep hatred for the [Mongolian] Revolutionary Party’s actions.

‘The way I found out my father was a lam is a very interesting story’

During the Soviet era, the people who visited Gandenteghchinlen (abbrev. Ganden) Monastery [4] had to be registered. My father often went to Ganden [5] to attend pujas from which sometimes he did not come home. So we wondered about what he was doing not coming home over night, but no-one knew the reason why, and no-one asked. That is the way things worked in those days. It was the 1970s. Most people were still very much afraid to go to Ganden to attend pujas. If they did go there, they felt self-conscious, uneasy, somewhat awkward as well as ashamed to meet others whom they knew and who were also visiting Gandan. The times were like that.

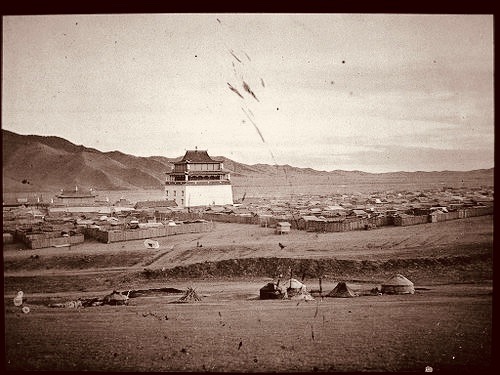

Baruun khüree or Gandentegchinlen (Ganden Monastery) in Urga (now Ulaanbaator) in 1913. Original photograph by Stéphane Passet (1875-1942). Rendered in sepia by C.Pleteshner. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gandantegchinlen_Monastery#/media/File:1913_in_Khuree.jpg

I knew an old woman who lived at Ganden. She was a Buddhist practitioner. I always went to see her to ask her things.I first started visiting Ganden when my first husband died. I felt nothing was better to eliminate my sadness than visiting Ganden. I would attend a puja and then feed the pigeons with my children after my husband’s death. One time I asked the old woman to do ‘Himorlin san’ for me, but she refused saying that I should ask my own father to do it for me instead. She said, ‘Compared to your father, I have less knowledge. Go and ask him.’

This is how I found out my father was a lam. I only found out a few years before he died. At that time, I was already around 40 years old. [6] Before this, I had never considered or worshipped my father as a lam. My brother’s wife was an intelligent and perceptive woman. She had always asked my father to come to visit their home. She knew he was not an ordinary man. It turns out that she was the only one amongst all of our relatives to benefit from his knowledge. I felt so much pity for my father’s fate. I completely changed my attitude towards him. I tried to change his clothes [buy new clothes for him] as often as I could afford to do so, and I started asking my father to come to visit to do puja for myself and my children too.

It is such a relief being able to tell this story, so unimportant as it is to others. What do we do with all these stories of suffering in our hearts? Speaking helps bring such things out from the darkness into the light. I have never told these things to anyone other than Narantsetseg. [7] I am so happy to finally have been given the opportunity to do so here .

This account, along with similar narratives by other ‘socialist era’ Mongol women in my collection, point to the fact that there were Buddhist women-practitioners ‘in residence’ at Ganden monastery during the Soviet socialist era from whom Mongol women sought guidance and advice. Whilst the actual trajectories of these conversations remain confidential, so too the advice, there’s little doubt that certain Mongol women who lived within the Gandentegchinlen precinct knew who was who. Their power lay in terms of this and other knowledge, their discretion and advice. In Mongolian culture, it seems that women may have always been situated in close proximity to religious men, even during the socialist times in (Outer) Mongolia.

For the Record Story No. 2

There is a particular story in my life that I have not shared with others before, and that I have kept always only in my heart. But I would like to share this with you now. I always felt such pity for my parents. The 1950s was the peak of the collectivisation movement. My father was the leader amongst his own relatives and was taking on a lot of responsibilities for them. He did not like the collectivization and was trying to delay as long as possible joining the local collectivisation cooperative.

As a result, local people started referring to us as ‘an obstinate family.’ Finally, our family was forced to give away all of our livestock. I was so shocked when I saw all the livestock being taken away, leaving the holding enclosure completely empty, that day I arrived home from school. It was the first day of the winter holidays. Each member of the co-operative was only allowed to own a few, a small number of animals, per person. With all their animals gone, my parents were then given the job of raising two-year old cattle, all of which had scabies and mange. This was their punishment for delaying the formation of the local cooperative.

In the bitter cold of winter, both my parents had to work without any rest to take care of these young cows, all of which were sick and had scabies. If any died, they had to pay for it by replacing it from their own livestock. This was such a bitter experience for them. I will never forget how hard the conditions were for them at that time. This experience has never left my heart, and has resulted in a bitter dislike of the (socialist) system for my entire life. The (Mongolian) Revolutionary Party made people suffer so much, including my own parents. [deep sobbing].

This experience and the suffering it caused has stayed deep in my heart, like a thorn hurting me whenever I think of my parents. All I can do now for my own relief is to pray for them and to repay their kindness to me by keeping contact with the monastery to help the Dharma flourish. Truly, Buddha Dharma[8] is my one relief.

Footnotes and other explanations

[1] Khalkha Mongol women (Mongolian nationals) born in Mongolia between 1930 and 1964.

[2] In keeping with the schema used throughout this book, italicized text indicates the actual (or translated) words spoken by Mongolian women themselves. Additional words or explanatory notes in parentheses […] are my own.

[3] See the University of Cambridge’s bilingual Oral History of Twentieth Century Mongolia Project for other oral histories collected from Mongolian people in Mongolia (~2007-2008). This wealth of first-person narrative is the result of a research project overseen by Caroline Humphrey and Christopher Kaplonski. To my knowledge, none of the 32+ Khalkha Mongol women who are participating in my (now longitudinal) ethnographic study have contributed to this other general and larger oral history repository. My initial study participant recruitment strategy, as outlined in the previous article, is more focused.

[4] Mongolian Cyrillic: Гандантэгчинлэн хийд, Gandentegchinlen khiid, short name: Ganden Mongolian: Гандан.

[5] Gandentegchenlin khiid (Tibetan. dga’-ldan theg chen gling, R-912): its main assembly hall was a stable from 1938, but [in 2008] it functioned again as the main assembly hall of Ganden. The relics temples of the 5th and 7th Bogds have survived the purges, and in 1944, when Ganden was partly reopened, seven lamas started to hold rituals in these temples. The relics temple of the 8th Bogd is a library now, while in Didinpowran high-ranking lamas hold ceremonies, and lamas read texts at the request of lay people. The monastery contains numerous old artifacts brought here by old lamas from all parts of the country. Ganden’s monastic schools (datsan) were demolished or burnt in 1938, but several of them were rebuilt after the democratic changes.

Migjid Janraisegiig süm (Janraiseg datsan, Tibetan. mig-’byed spyan-ras gzigs-kyi grwa- tshang, R-913): it was used as a military barrack from 1938. A huge amount was offered to pull down the temple in the 1950s, but nobody applied. From the 1950s it functioned as the State Archives. Today, it houses Avalokitēśvara’s new statue, which was consecrated in 1996.

Tsagaan suwragiin khural (Jarankhashariin suwraga, Tibetan bya-rung kha-shor, NR-960) has not remained. The Television tower stands on its site today.

Source: Krisztina Teleki (2012) Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khuree, p227. http://real.mtak.hu/23767/1/Kristina%20nom.pdf. Accessed 14 August 2018.

[6] This locates the events somewhere around 1980.

[7] A pseudonym for one of the other Khalkha Mongol women in my study.

[8] Embedded in this article is the notion that ‘Buddhism’ as a devotional practice and way of life is of some value for those involved, whether in the past or the present. Not all of you (my readers) subscribe to this perspective, so I need to begin ‘unpacking’ for you at least some of this embedded-ness, especially if you are to appreciate the depth and ongoing pervasiveness of personal suffering reflected in the above narratives of loss orated by socialist era Mongol women.

As an introduction, I draw on the words of someone who is more versed in explaining to ‘westerners’ such things:

Many people erroneously think that Buddhism is a religion similar to Christianity, Judaism, or Hinduism that worships a supreme being or supreme beings who are separate from humankind. But Buddhism is very different from such theistic religions, be they monotheistic or polytheistic. While some aspects of Buddhism, such as the excistence of holy texts, sacred places, temples, an ordained Sangha [cf. to a community of practice], established rituals and a rigorous ethical code, may make it appear similar to a religion, it is more accurately described as a way of life that is based on teachings of the historical Buddha, who lived sometime between the sixth and fourth century BCE. Buddhists do not worship the Buddha in the way that Christians worship God, as a supreme being with the power to grant them salvation or send them to eternal damnation. We do not attain Buddhahood or Enlightenment through divine grace; we attain it through persevering with practices that give us insight into our minds and the nature of reality. No one can become God, but by putting the Buddha’s teaching into practice, we can all become Buddhas. Extract from ZT Rinpoche’s (2013) Tara in the Palm of Your Hand. (2013 Wind Horse Press)

Landscape 06: For the Record was researched and written by Catherine Pleteshner.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating the photographs or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2024. CP in Mongolia. This post Landscape 06: For the Record is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 14 August 2018. Last updated: 20 June 2022.