In recent months I have been immersed in translating Zava Damdin Lama’s song lines (Skt. doha) and stanzas for his first major scholarly reference book to be published in the English language.

This photograph was taken at Zava Damdin Lama’s birthday celebrations on 10 September 2014 at Delgeruun Choira in Delgertsogt Sum in Mongolia’s Dundgovi (Gobi) just prior to our starting the serious development of The Great Nenchen manuscript. I am seated on the left behind L.Pagchog and L.Sampel.

The above archival photograph was taken by the Mexican cinematographer Gabriela Reyes Fuchs. It appears here with permission from the Zava Damdin Institute of Mongolia.

___________________________

What follows is an edited extract from my interpreter’s notes from the first edition of The Great Nenchen (2015) by Zava Damdin Lama (1976 – ):

“During the four years (2007–2011) of his solitary Nenchen retreat in a small Mongolian ger in the grounds of Delgeruun Choira, the Mongol Buddhist scholar-poet Zava Damdin Lama (1976– ) composed an extensive collection of songs using five different scripts: traditional Mongolian vertical script (Mongol Bichig), Mongolian Cyrillic, Tibetan, English and Mandarin-Chinese. A selection of these songs has been translated and interpreted into the English language for the first hardcover edition of this book.

As local Mongol traditions continue to intersect with globalising modernities, one of the primary objectives of this literary-art work is to document important aspects of Zava Damdin Lama’s indigenous, educational and cultural inheritances—themselves a complex of orally-transmitted lineage continuities, each of whom have shaped and continue to inform his own considerable output of contemporary works.

In terms of a social anthropology of religion, one can study the interwoven complexities of contemporary post-soviet socialist Mongol Buddhist culture in a variety of ways, with extensive reading of previous ethnographic interpretations by learned others being one of the illuminating and therefore salient modes. Since the cessation of soviet socialism in Mongolia during the early 1990s, a myriad of ways by which any one individual can express their contemporary Mongol-ness have emerged. The original songs and finely-detailed watercolours in this book reflect aspects of the Mongol scholar-poet Zava Damdin Lama’s chosen and very particular way.”

“My sincerest wish for those of you interested in developing a more locally-nuanced understanding of contemporary Mongol Buddhist culture, is for you to gain such an appreciation—of what it is to be a Mongol, a Gelugpa Buddhist and a practicing Lama—through exploring the interplay between Zava Damdin Lama’s own intimate artworks and songs.

Whilst some readers may already be familiar with (Gelugpa) Buddhist epistemologies, they may have yet to develop an appreciation of how such a belief system can be expressed temporally in ‘songs’ with Mongol cultural valencies. This book is our first attempt to address the paucity of such authentic and credible published resources.

To facilitate a better understanding by readers of Zava Damdin Lama’s location at the contemporary (rather than historical) Mongol-Tibetan cultural interface, and to foreground the Mongol aspect of his Gelugpa-ness, (an area of scholarly study that requires far more investigation) additional contextualising information drawn from nomadic as well as Buddhist philosophies has been prepared and included.

We completed the English language transcript in Mongolia during the Autumn months of 2014. Whilst we worked, the first snow heralding the onset of Mongolia’s long Winter arrived, and an atmosphere of deep mutual respect and good humour blossomed as we waded deeper into the considerable complexities associated with translating and interpreting the texts. As we debated semantic nuances, and tussled with the challenges inherent in the iterative ‘negotiating of meaning’ process, what immediately became apparent was our shared intention not to disengage with, or to overwrite the important cultural and other meanings embedded in the original Mongolian Nenchen text.

From this editorial emphasis emerged a literary solution; that of articulating and relying on footnotes throughout the English-language edition as both an explanatory and contextualising device. These concise explanations and clarifications allude to far more complex and relevant analyses of both Mongol nomadic culture and Mahayana-Vajrayana Gelugpa Buddhist epistemologies. Such illuminating commentaries often conveyed in the form of a short story or tale were generously (and graciously) offered by Zava Damdin Lama during the weeks we worked together on a daily basis at his home in Nukht. One by one, we resolved the many details associated with accurately and appropriately interpreting the Nenchen text. Whilst Zava Damdin Lama was in all instances the final arbitrator, this interpretation-transfer into the English language process raised for each of us a plethora of unanticipated questions and issues—linguistic insiders and outsiders alike—all of which had to be negotiated (in terms of meaning) or in some way satisfactorily resolved if we were to complete to our mutual satisfaction The Great Nenchen translation task”.

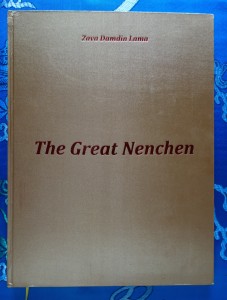

The Great Nenchen (2015) by Zava Damdin Lama, silk cloth, embossed back cover, author’s stamp (Manchu)

“Whereas the transliteration and translation processes were reasonably straight-forward, ‘interpreting’ complex Mongol concept words anchored in nomadic and Buddhist epistemologies into English, as well as reshaping them into poetic forms, song lines and stanzas using English-language syntax and semantics, was by far a more complex and nuanced undertaking. As my esteemed Mongol colleagues offered initial word-meanings, I was drawn deeper into a traditional, contemporary and sophisticated Mongol socio-Buddhist way of life.

Whilst embedded meanings may be taken for granted by a select few learned Mongol-Buddhist scholars, such assumptions simply cannot also be drawn by those of us lacking a deeper indigenous knowledge of not only the Mongol’s language, but also the actual cultural, social and spiritual contexts within which it (the language) is ‘socially performed’ (See: Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life. New York Anchor Books).

I hope these brief notes offer you some insight into the motivation and atmosphere of our work, and that this abridged account of personal experience, cultural background and other explanations offered in the footnotes of the book will be of value to an anthropology of contemporary Mongol-ness and the study of the ‘Mongol-Tibetan’ philosophical interface. ”

Translation is always an interpretation into another culture.

Citation: The Great Nenchen (2015) by Zava Damdin Lama. (First Edition) Translated by Catherine Pleteshner and Erdenetsogtyn Sodontogos (Zava Damdin Sutra and Scripture Institute, Ulaanbaatar Mongolia). ISBN 9778-99962-4-344-8. pp.119-123 (Edited extract reprinted with permission from the publisher).

Note: Although Erdenetsogt Sodontogos‘s culturally illuminating translator’s notes are not also included here, it is nonetheless very important to acknowledge her contribution, given that our translation of Zava Damdin Lama’s songs for The Great Nenchen was unquestionably a collaborative effort. In her professional diplomatic life, E. Sodontogos was, at the time of writing, the President of Mongolia’s (cf. Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj) multi-lingual personal interpreter. In 2014 she also established the YeS Happiness Foundation, after the tragic and unexpected loss of her own two young sons. The mission of her new organisation is to help Mongolian children who are experiencing considerable hardship amidst the ongoing socio-structural turbulence of Mongolia’s post-soviet socialist democratic reforms. We wish her and her associates the very best with this important service-to-local-community in Mongolia effort. These days (2025) Sodon is the Director-General of Mongolia’s Montsame National News Agency.

_____________________________

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone using or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

End of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2025. CP in Mongolia. This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 3 May 2015. Last updated: 26 December 2024.